What is a still life and why are they important?

The term ‘still life’ describes an artwork, most often a painting, of inanimate objects. They commonly depict bowls of fruit, blooms of flowers or piles of books placed on a table. Whilst their depictions might seem simple, or even random, they are in fact meticulously planned and full of coded meanings.

When and why did the still life genre start? And what do they mean?

Still life painting flourished in Europe during the first half of the 17th century. Old Master artists like Caravaggio in Italy and Diego Velázquez in Spain experimented with it, but it was Flemish and Dutch artists, including Frans Snyders, Jan Brueghel the Elder, Rachel Ruysch and Jan Davidsz de Heem, that took still life painting to new heights.

These artists used still life painting to reflect their changing surroundings, opinions and morals. Objects such as flowers and skulls could be used to represent popular philosophical teachings about the nature of life and death. For example, some works celebrated life through blossom, whilst others used rotting vegetables or hunted animals as memento mori — reminders that everything, and everybody, dies.

Bibles and crucifixes were representative of the power of the church, which had recently experienced the protestant reformation. Luxury items, like silver candlesticks, were an analogy for the rise of the bourgeoise — a newly minted middle class made rich through maritime trade. Exotic fruits, meanwhile, were suggestive of an interest in travel and biology. Collectors could pick works that contained symbols which best reflected their interests and beliefs.

Furthermore, still life paintings were also an exercise for an artist’s showmanship. They could use the fuzzy flesh of a fruit, the silky fur of an animal or even a reflection on water in a clear glass to show off their dazzling skills for detail and realism.

How did the genre of still life art evolve?

During the 19th century, Paul Cézanne reinvigorated still life painting, creating harmonious compositions of olive jars, lemons, apples and printed cloth that evoke a sense of place — in this case, his home in the south of France.

In the first half of the 20th century, Giorgio Morandi revolutionised still life painting again, this time by creating pictures of banal boxes, jars and jugs in subtle tones that have been celebrated as both poetically tranquil images of modern life and critiques of the rise of consumerism.

The latter idea was built upon in the second half of the 20th century by Andy Warhol, who painted, printed, sculpted and photographed numerous still life images of fruit, flowers, and most famously, cans of soup, which examined mass production.

Are there any contemporary still life artists?

Yes, absolutely. The young American painter Nicolas Holiber has recently turned his hand to still life painting. Inspired by the birth of his first child, he creates his own version of memento mori paintings that feature platters brimming with skulls and burning candles. They blur the lines between representation and abstraction with their bright colours and impasto surfaces.

Kristof Santy, from Belgium, is another artist breathing new life into the genre. ‘I invent nothing, I just rediscover,’ he claims. His still life paintings, which draw heavily on 19th and 20th century folk art, apply a modern twist to the usual, seemingly mundane range of objects to choose from. Instead, he incorporates toasters, cheese graters, cans of sardines, cigarettes and coffee pots into his works, which look for beauty and design in everyday things.

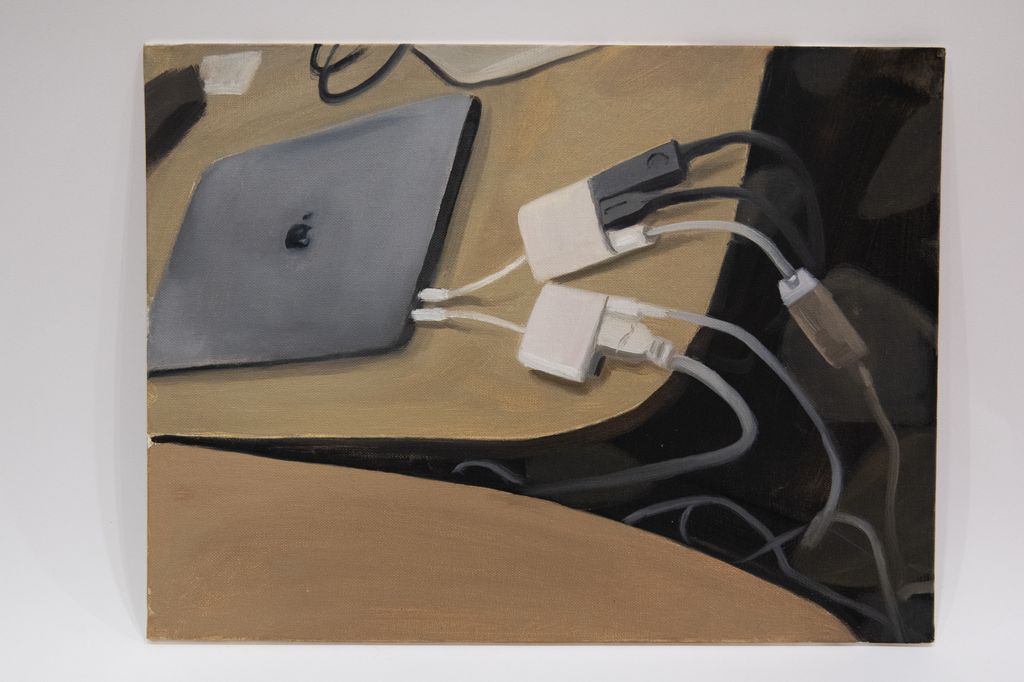

Another contemporary still life painter with a rising reputation is Mauro C. Martinez. The Mexican-American artist is helping drive the tradition forward by painting and sculpting symbols of modern technology, like games consoles, computers and tangled headphones and chargers. Martinez uses these objects to investigate the role of digital imagery in the 21st century world. As well as a string of successful solo shows at Unit London, he has also placed work in world-famous public collections in places like Hong Kong, Los Angeles and Lebanon.

This new generation of contemporary still life artists are not only keeping the tradition alive, but also pushing it into new territories and evolving the ways in which paintings that don’t contain people can still search for what it means to be human.